A Dramaturgy of Civilisation

THE COURTESAN AND THE SAINT

A Dramaturgy of Civilisation

A mirror does not interpret. It shows

For those who could not attend the launch, you can read and engage with it here. This is a typed copy from my draft/read.

What are these poems about?

The poems are meditations on Dharma.

Every one knows what Dharma is, still, it’s precisely in the simple knowing that it remains invisible.

I will not venture into the invisible and will only say that this collection holds a mirror to time; not to any single moment but to the long arc from the courts of Hastinapur to the coded grids of the present. What the mirror reveals is not progress. It is a pattern: the thread weakens, the court forgets, sovereignty detaches from its sacred ground, and the world fragments.

What it also reveals; held in the glass if you look steadily enough, is that the ground itself does not disappear. It waits.

The Sutradhar

The sutradhar in classical Indian theatre is the thread-holder. He introduces the play, frames the world, establishes context. He is not a character inside the drama. He is the one who holds continuity. In civilisational terms, the sutradhar is tradition itself — the unseen continuity that prevents fragmentation. Once the sutradhar disappears, narrative collapses into disconnected scenes.

This collection declares that civilisation is theatre, but not fiction. His opening question is not dramatic; it is ontological. What is this light? What engine, what will, / manifests and unmakes? He does not answer. He holds the question open and steps aside.

What follows is not a sequence in the narrative sense. It is a diagnostic: a civilisational reading conducted through figures both mythic and contemporary, each one illuminating a different stage of the same fracture.

Dushyant— the king who forgets

Dushyant is the first figure and the paradigmatic one. A king who forgets his vow — not through malice but through the simulated amnesia that power produces. The blood that seeped / into the earth, / nourishing the roots of sorrow, / will rise again — / not as vengeance, / but as the inevitable consequence / of a truth denied. His forgetting is not personal failure. It is civilisational. When sovereignty loses its memory of dharma, the consequences do not disappear; they merely wait for the son.

Memory loss is not romantic. It is simulated amnesia. Civilisation forgetting its own vow to dharma is Dushyant.

Shakuntala in Court — who can be the king

Shakuntala enters the court not as a supplicant but as the memory of dharma itself, demanding recognition in the seat of power. Her voice is one of the collection’s most striking — not as a broken woman, but one / possessed of remarkable moral strength. This is not romantic drama.

Now recognition must happen in public. Shakuntala does not plead sentiment. She asserts truth in the king’s court. The court is sovereignty. The king is power. The woman is memory of dharma. This is confrontation between living truth and institutional authority. When power forgets its vow, the feminine principle of continuity must appear in court.

If the court rejects her, legitimacy fractures. Dharma breaks.

Draupadi in Court intensifies the crisis

Draupadi is not asking for recognition. She is demanding justice.

The court is silent. The elders are silent. Sovereignty has decayed into spectacle. This is not personal humiliation. It is systemic collapse of dharma. When Draupadi is disrobed at the prompt and enthusiasm of Karna, it is civilisation being stripped of sacred protection. The Mahābhārata war follows. The collection makes its first major argument here: when the court fails truth, violence is not an aberration. It is the structure’s inevitable consequence.

Was I won in accordance with dharma? / Or was dharma twisted to suit the whims of men? The question has not dated.

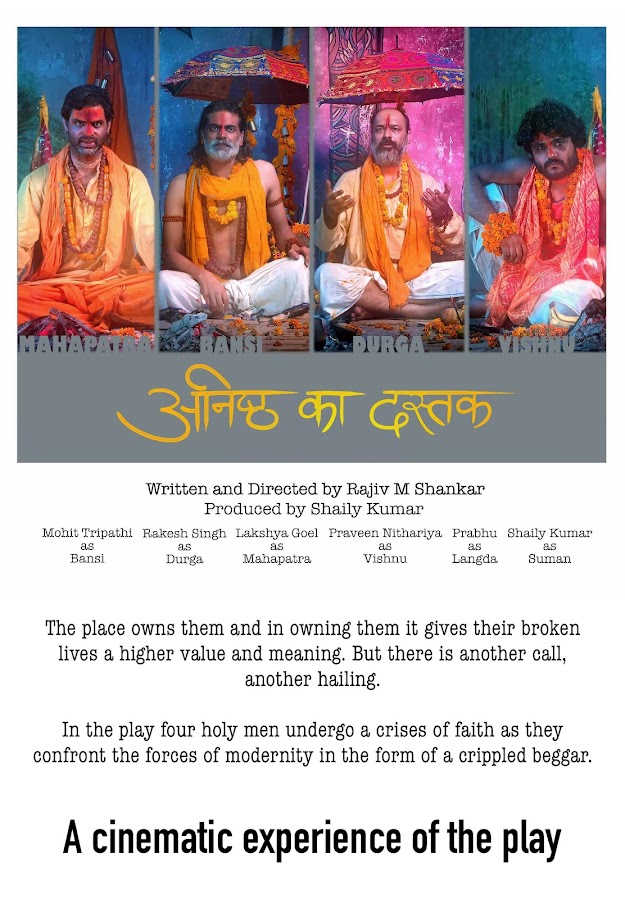

The Courtesan and The Saint

The courtesan represents beauty without sacred anchoring. The saint represents sacred insight without institutional power. Their meeting is the diagnosis: what was once unified is now in pieces. Art detached from dharma. Power detached from memory. Knowledge detached from Being. This is diaspora of the sacred.

Mohini and Tulsidas turn on the same question from both sides — whether renunciation that cannot accommodate the world has truly understood the world it left behind; whether beauty that circulates outside the sacred has truly escaped it. The courtesan’s long monologue is the most direct voice in the collection, asking the question the institutions cannot: What does it mean / to ‘be’ a woman in our times? Can dharma be found in denial, / or must it be embraced in the heart of chaos? Neither has the full answer. That is precisely the point.

What follows is a civilisational diagnosis: Thread weakens. Memory fails. Truth enters court. Power refuses. Humiliation of dharma. War inevitable. Modern fragmentation. Machine intelligence ascends. Tiger caged. That is the threshold: where philosophy must become practice.

The Brahmin - the Whole / was observing itself

In these poems, “Brahmin” is not caste sociology. It is archetype.

The Brahmin represents: custodian of speech; guardian of ignition; the one who knows that Vāk and Brahman are not separate; the one who preserves continuity through oral transmission.

This is not about social hierarchy. It is about existential responsibility.

The Brahmin is dangerous when hollow. He becomes ritual technician without fire. He becomes memoriser without vision. But when living, he is the sutradhar in embodied form.

The poem is the collection’s most compressed statement of the archetype. A gardener’s boy, tending seeds, is told he is a Brahmin — not by caste but by act: when you water / and wait / for the seed to grow. The boy looks at the garden and grasps the earth as if / the Whole / was observing itself. The poem is brief because it needs to be. It does not argue; it demonstrates.

In this collection the Brahmin stands at the beginning as living source and at the end as endangered species.

The collection now moves inward.

The interior poems — Kingfisher, Change, The Arrival, God, Death — move the collection from civilisational diagnosis to existential encounter.

Kingfisher is a flash. Sudden descent. Precision. Silence before plunge. It is attention. The kingfisher does not theorise the river. It enters it. If Soma is ignition, the kingfisher is the act of direct perception before conceptual overlay. No court. No ritual apparatus. Just strike. It stands against abstraction without experience.

Change is destabilisation. The text does not treat change as progress by default. It asks: what changes, and what remains? Civilisation changes. Institutions change. Power changes. But if Being does not remain centre, change becomes drift. This poem challenges romantic continuity. It forces the reader to confront impermanence without surrendering ground.

The Arrival is ambiguous. What arrives after civilisational collapse? Not empire. Not technology. Something subtler. Presence. Recognition. Arrival in this arc means awareness breaking through forgetfulness. It is not migration. It is awakening. It is not acquisition of knowledge. It is removal of obstruction. Neither modern literature nor the engineers of the age can guide the reader through what is coming — not because they are inadequate but because the veil itself has shifted.

God strips anthropomorphic comfort. God is not elsewhere. Not tribal possession. Not decorative metaphysics. The divine is the condition of existence, not an object. “God” here functions as the unnamed ground, not doctrinal deity. If you hold on to / an image of God, / you cannot see Him, / and He / cannot see you. What remains after the image is removed is not absence but dissolve — into the silence that precedes sound.

Death is the final test of ontology. If Soma is living ignition, if Brahman is ground, if Vāk discloses Being — then death is not annihilation but transition of form within ground. If the ground is lost, death is terror. If the ground is known, death is boundary event. This movement is from civilisational critique to existential stripping. Are we living from that ground now, or merely arguing about its antiquity?

Letters to Anamika

Letters to Anamika is the collection’s most intimate movement — a series of aphoristic transmissions addressed to a beloved, in the tradition of Vedantic instruction. Each opens Beloved and moves without ceremony into the deepest water: You are the light of that light. / Atman is the voice of Brahman, / and its essence is light. These are not love poems in the conventional sense. They are love directed at consciousness itself, spoken by one who has looked at the ground directly and is trying to show another where to look. Words are not made of letters, / nor sentences of words. / Meaning shines forth from the whole. This is not linguistics. It is the Vāk doctrine — speech as the disclosure of Being — rendered in the simplest possible terms.

The Clerk

The Clerk is the collection’s most quietly devastating lyric. A broken man, defeated, unable to rise. The question it holds: whether the search for beauty in the ordinary carries within it the seed of regeneration. It does not answer. It holds the question open the way the sutradhar held his.

The Holy and the Sovereign / The Tale of Tales

The extended sequence of The Holy and the Sovereign and The Tale of Tales is the collection’s philosophical centrepiece. The dialogue between the Englishman and the Brahmin boy is not a debate about the past. It is a contest over who currently holds the living Soma — the value that animates a civilisation, the elixir of sacred knowledge.

The Englishman represents imperial rationality, modern state power, technological conquest, and textualised knowledge. He wants to “master” the Veda as sovereign. He approaches it as something that can be possessed.

The boy represents living Vedic consciousness. Not ritual detail, not academic commentary, but the inner grammar of culture.

The boy: Culture is not external ornament. It is the weave that binds meaning. Ritual is not superstition. It is the daily ignition of value. Soma is not a plant alone. It is the distilled essence of civilisation. Speech and Brahman are united at the origin.

The Theft of Soma story is the key metaphor. Soma is stolen. Speech is traded. Ritual is hollowed. Substitutes are created. Clarified butter replaces true Soma. The appearance remains. The essence is gone.

That is the boy’s indictment of modernity. When he tells the Englishman that the falcon has flown to Europe and America, guarded now by Science and Art, he is not denying Western achievement. He is saying the centre of ignition has moved.

The real argument in that dialogue is this: Soma equals living value — what gives meaning its power, what one organises life around. Brahman equals that luminous ground. Vāk equals the medium through which reality is disclosed. When ritual becomes empty repetition, when speech becomes hollow, when sovereignty divorces itself from sacred ground, civilisation fractures.

The Englishman in the dialogue is not stupid. He pushes back. He claims modernity has discovered its own Soma. He asserts conquest from sea to sea.

The boy responds with a devastating question: Are you guardian or new Vritra?

The Veda is not a text to be translated. It is a living ignition process. Without that ignition, ritual and empire both decay. The Englishman and the boy are not debating history. They are debating who still holds the living Soma. That is the axis.

Zoo, Nameless, The Spirit of Machines

Zoo is the collection’s central modern image. The tiger is no longer sovereign. He is reduced to an artefact. His claws, teeth, roar, intelligence, cosmic lineage are remembered, but he stands behind bars. This is not about an animal. It is about civilisation after severance from its ground. The tiger once shaped by the wild becomes an exhibit. His body survives. His essence withdraws. What happens when the spirit withdraws but the structure remains? That is a civilisational warning.

Nameless intensifies it. A god approaches. Should man fail to see him, calamity follows. The language becomes electric, charged, destabilised. Something is coming, but perception is dulled.

The Spirit of Machines makes the warning explicit. Intelligence gathers man and locks his spirit to its will. The sweetness of technological seduction replaces living fire.

Earlier in the collection, Soma is stolen and replaced by substitute ghee. The appearance of ritual survives. The ignition does not. Later, industrial civilisation replaces sacred orientation with data and profit. By the end, the tiger is in a cage and man is enthralled by machine intelligence. The two poems are not mythological commentary. They are diagnostic.

They say: you have replaced wild fire with enclosure, living Soma with substitute, light of Being with manufactured light. The question is whether the wild ignition can return, or whether civilisation will remain a zoo of its former power.

Voices, The Leaf, Crumpled Notes

Voices, The Leaf, and Crumpled Notes are the collection’s most philosophical lyrics — brief, exact, concerned with the nature of language itself. Voices observes that what we claim as our own thought is always already saturated by what was there before us: voices never belong to anyone. The Leaf moves through a chain of nested dependencies — leaf, light, lamp, electric current, tungsten — asking at each step: who holds them? Crumpled Notes finds in the reject pile of the writing desk something that was never truly erased: there lies a trace, / undoubting, / though lifeless and cold. Together they constitute a meditation on what persists when the form is discarded.

Inukshuk

Inukshuk is the collection’s most geographically unexpected poem — an Inuit stone marker, a human-shaped cairn built from accumulated stones to guide travellers across featureless terrain. Two continents meet in its gaze. Metaphor slips into metonymy, / the self un-selfs itself. The stone is not a symbol. It is a sentinel — a form that holds its shape in cold silence so that those who come after can find their way. What the collection is doing, the Inukshuk is.

Jambavanta

Jambavanta is the ancient bear-king from the Rāmāyaṇa. In epic logic, he is primordial memory. He remembers earlier ages. He recognises Hanuman’s forgotten power. He awakens latent strength.

When invoked at the end of a modern poetic arc, Jambavanta represents civilisational memory that survives collapse. He is not nostalgia. He is continuity beneath rupture. The ground does not disappear when the structure built on it decays. Power is forgotten, not destroyed.

Danav and Rakshasa

Danavas are not simply “demons.” They represent titanic forces of power without alignment to ṛta. Raw intelligence, ambition, scale without dharma. In a modern reading, Danav energy resembles industrial magnitude without sacred anchoring. It builds, expands, consumes.

Rakshasa in epic tradition represents distortion of order, appetite unrestrained by dharma, intelligence turned predatory. If Danav is titanic force, Rakshasa is perversion of that force into devouring chaos. The poem speaks in the demon’s own voice — I came as convenience. / You prayed at my gate, / fed me your choices, / then called it “fate” — and its final inversion is the collection’s most devastating line: It wasn’t I who destroyed your kin. / It was the demon you welcomed in.

Together, Danav and Rakshasa name the forces that fill the vacancy left when sovereignty detaches from sacred orientation. Power persists. Order fractures.

The Song of Diaspora

The Song of Diaspora is the culmination. It closes the collection in three movements — Exile, Echo, The Unwritten. Diaspora is not merely geographic exile. It is metaphysical displacement. A people severed from soil. Language severed from source. Ritual severed from ignition.

Earlier, the tiger was in a zoo. Now civilisation is in diaspora.

The second movement asks whether the ancient threads still visit in dreams, or whether the past itself has forgotten those who long to return to it. The third movement finds, beneath the ash, something older than memory: the pulse before the word. Not lost. Not yet.

The poems form a progression: wild sovereignty; ritual hollowed; machine intelligence ascendant; memory figures appear; titanic and demonic forces dominate; cultural exile becomes condition.

This is not a random collection. The warning is not “return to past.”

The warning is: if Vāk is severed from Brahman, culture becomes noise. If dharma is severed from sovereignty, power becomes Danav. If intelligence is severed from Being, it becomes Rakshasa. If memory is severed from living transmission, diaspora becomes permanent. A civilisational amnesia.

The collection moves from the court to the forest to the market to the zoo to the digital grid to the tundra cairn to the diaspora. It holds all these places in relation the way the sutradhar holds all the characters — not by making them continuous but by holding the thread that runs beneath the discontinuities.

The mirror does not offer easy resolution. What is seen in it is both the fracture and the ground the fracture has not yet reached — and it keeps that open to you.

When Vāk is severed from Brahman, speech becomes noise.

When ritual is severed from ignition, it becomes performance.

When sovereignty is severed from dharma, it becomes domination.

When intelligence is severed from Being, it becomes machinery.

The poems know the difference.

Rajiv Mudgal